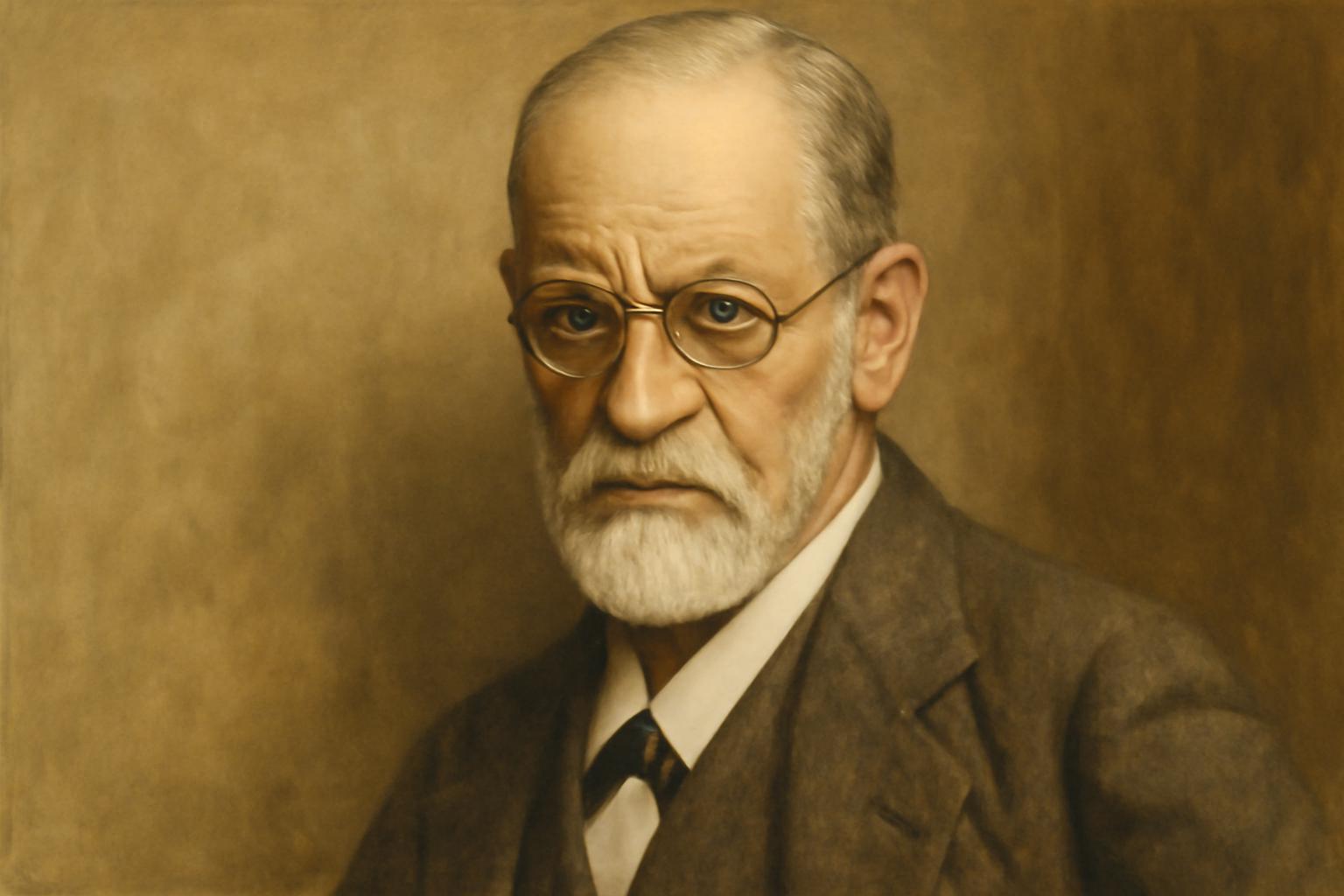

Sigmund Freud: Theories and the Birth of Psychoanalysis

Quick Summary

Sigmund Freud was the founder of psychoanalysis, a theory and therapy that explores how unconscious thoughts, early experiences, and inner conflict shape behavior. He introduced key concepts like the id, ego, and superego, as well as defense mechanisms and psychosexual development. Freud’s legacy remains central to psychology despite criticisms of his scientific rigor. His ideas continue to influence therapy, research, and our everyday understanding of the mind.

Early Life and Education

Freud was born on May 6, 1856, in Freiberg, now part of the Czech Republic. His family moved to Vienna when he was four years old, where he later enrolled at the University of Vienna to study medicine. Originally interested in neurology, Freud conducted research on cerebral palsy and aphasia. However, his growing fascination with mental illness gradually shifted his focus from physical causes to psychological explanations.[1]

The Start of Psychoanalysis

After completing his medical training, Freud traveled to Paris in 1885 to study under neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, who was known for his work on hysteria and hypnosis.[2] Freud observed how Charcot used hypnosis to treat patients with psychological symptoms that had no identifiable physical cause, which challenged Freud’s previous understanding of illness and sparked his interest in the unconscious mind.

These experiences deeply influenced Freud’s thinking about the origins of mental distress. Upon returning to Vienna, he collaborated with Josef Breuer to develop what became known as the “talking cure”—a method that encouraged patients to speak freely about memories and feelings, revealing repressed memories and emotional conflicts.[3] This technique laid the foundation for psychoanalysis.

The Foundations of Psychoanalysis

Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis, often called Freudian theory, laid the foundation for many areas of psychology.[4] His ideas focused on understanding unconscious processes, personality development, emotional conflicts, and the methods used to treat mental health issues.

The following is a brief overview of key concepts, which are explored in greater detail in our full post on psychoanalysis here.

1. The Unconscious Mind

Freud believed most of our behavior is driven by unconscious thoughts and memories. By exploring the unconscious, people could gain deeper insight into their emotions and behaviors.[5]

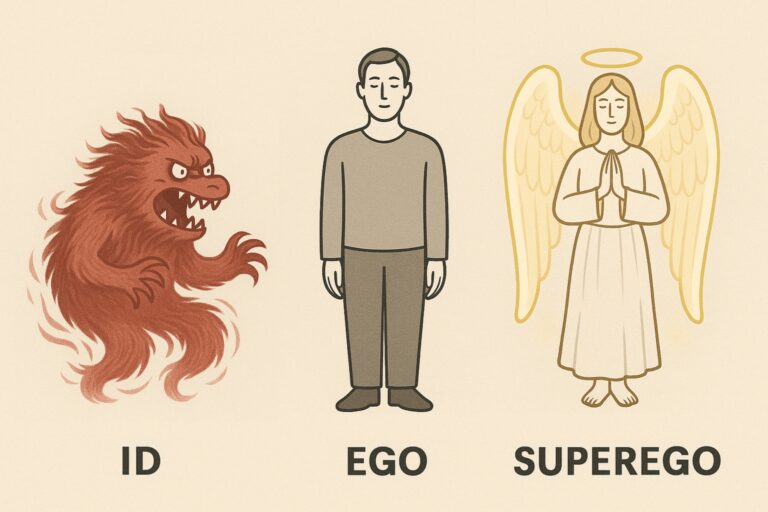

2. The Structure of Personality and the Mind

Freud’s structural model of personality and the mind includes three interacting components:

- Id: Instincts and desires seeking immediate pleasure

- Ego: The rational self that balances demands and reality

- Superego: The moral conscience aiming for perfection

The ego constantly works to manage the tensions between the id’s desires and the superego’s rules.[4]

3. Defense Mechanisms

To manage anxiety arising from inner conflict between the id, superego, and reality, the ego uses defense mechanisms.[6]

These are unconscious strategies like:

- Repression: Pushing distressing memories away

- Denial: Refusing to accept reality

- Projection: Blaming others for personal feelings

- Sublimation: Channeling impulses into positive activities

Everyone uses defense mechanisms, but over-reliance on them can cause emotional difficulties.

Learn more about how defense mechanisms work in our full post here.

4. Psychosexual Stages of Development

Freud believed childhood development moved through stages focused on different areas of pleasure[7]:

- Oral Stage (0–1 year): Mouth-centered (feeding, sucking)

- Anal Stage (1–3 years): Control over bowel movements

- Phallic Stage (3–6 years): Awareness of gender and family roles

- Latency Stage (6–12 years): Social growth and learning

- Genital Stage (12+ years): Mature adult relationships

Unresolved issues at any stage can cause a person to become stuck in certain behaviors or emotional patterns later in life.

5. Dream Interpretation

Freud viewed dreams as reflections of hidden desires and conflicts[8]. By analyzing dreams, he believed people could uncover important truths about their unconscious mind.

6. Psychoanalysis as Therapy

Freud’s method of psychoanalysis involves helping patients explore their unconscious through techniques such as:

- Free association: Encouraging patients to say whatever comes to mind

- Dream analysis: Exploring symbolic meanings of dreams

The goal is to bring hidden feelings into awareness, helping people heal and grow emotionally.[9]

Criticisms and Controversy

Freud’s theories have been criticized for placing too much emphasis on sexuality and for lacking scientific evidence. For example, psychoanalyst Karen Horney argued that his ideas were overly focused on male psychology and ignored cultural and social influences on personality. She also believed that neurosis stems more from early relationships than from repressed sexual conflicts.[10]

Philosopher of science Karl Popper also challenged Freud’s theories, arguing that they were not scientifically testable. He claimed that psychoanalysis could be used to explain almost any behavior after the fact, making it unfalsifiable, a key criterion for distinguishing science from pseudoscience.[11]

Despite these criticisms, Freud’s influence on modern psychology remains significant, with many later theories building on or reacting to his work.

Freud’s Legacy

Despite the criticisms, Freud’s influence can be seen across psychology, therapy, art, literature, and even everyday language. While some of his theories have been challenged or updated, his focus on the unconscious mind and emotional development remains foundational in understanding human behavior.[12]

Major Works by Freud

- The Interpretation of Dreams (1900)

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905)

- Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920)

- Civilization and Its Discontents (1930)

Later Life and Death

In 1938, Freud fled Austria due to Nazi persecution and moved to London. He continued working until his death from cancer on September 23, 1939. His London home is now the Freud Museum, dedicated to preserving his legacy.

References

- Jay, M. E. (2025, May 2). Sigmund Freud. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sigmund-Freud

- Ellenberger, H. F. (1970). The discovery of the unconscious: The history and evolution of dynamic psychiatry. Basic Books.

- Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria. Franz Deuticke.

- Freud, S. (1961). The ego and the id. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 19, pp. 12–66). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1923)

- Freud, S. (1957). The unconscious. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 159–215). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1915)

- Freud, A. (1946). The ego and the mechanisms of defence (C. Baines, Trans.). International Universities Press. (Original work published 1936)

- Freud, S. (1953). Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 7, pp. 123–246). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1905)

- Freud, S. (1953). The interpretation of dreams. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vols. 4–5, pp. 1–627). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1900)

- Freud, S. (1963). Introductory lectures on psycho-analysis. In J. Strachey (Ed. & Trans.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vols. 15–16, pp. 1–463). Hogarth Press. (Original work published 1916–1917)

- Horney, K. (1937). The neurotic personality of our time. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Popper, K. (1963). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. Routledge.

- Gay, P. (1988). Freud: A life for our time. W. W. Norton & Company.