Ivan Pavlov: Discovery of Classical Conditioning and its Impact

Quick Summary

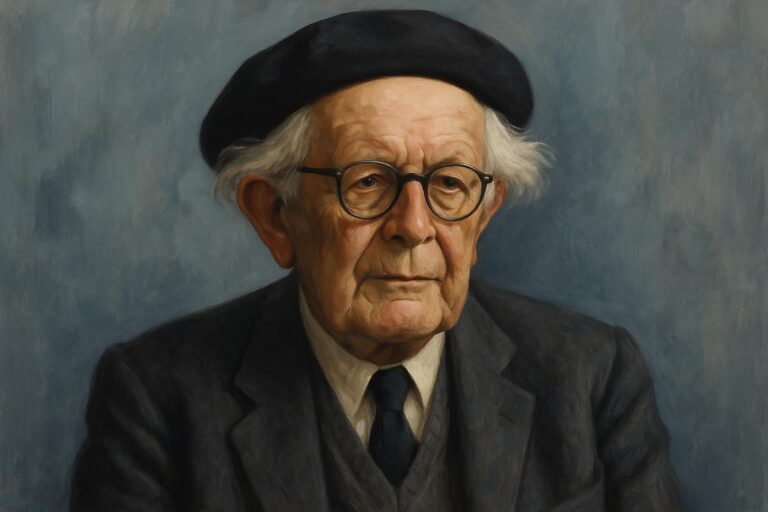

Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936) was a Russian physiologist who revolutionized psychology with his discovery of classical conditioning (aka Pavlovian conditioning), a process in which an organism learns to associate a neutral stimulus with a meaningful one. His research demonstrated that behaviors could be conditioned through association, transforming our understanding of learning and leading to the development of behaviorism. Pavlov’s famous dog experiment is one of the cornerstones of psychology today.

Early Life and Scientific Career

Born on September 14, 1849, in Ryazan, Russia, Ivan Pavlov originally pursued theology but switched to science after being inspired by his experiences in medical school. He studied medicine at the University of St. Petersburg and began his career researching the digestive system, with a particular focus on the salivary glands and reflexes.[1] These early studies laid the groundwork for his later breakthroughs in both physiology and psychology.

The Famous Experiment (Classical Conditioning)

Pavlov’s famous experiment with dogs is arguably one of the most famous in psychology. While studying digestion, he observed that dogs began salivating not only at food but also when they saw the lab assistants or heard the sound of footsteps. This led him to question how an animal could learn a new behavior in response to a neutral stimulus.

Pavlov conducted a controlled experiment where he used a metronome (not a bell, contrary to popular misconception) before presenting food to the dogs. After several repetitions, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the metronome, even when no food was present. This showed that an animal could learn to associate an unrelated stimulus (the metronome) with an automatic response (salivation).[2]

The process he discovered is called classical conditioning (aka Pavlovian conditioning), a form of learning in which an organism comes to associate a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus, eventually responding to the neutral stimulus in the same way. For Pavlov, the neutral stimulus (metronome) became a conditioned stimulus, and the dog’s salivation became a conditioned response (aka Pavlovian response).

Learn more about classical conditioning in our detailed post here.

Criticisms

While Pavlov’s work was groundbreaking, it has faced several key criticisms over time. Some psychologists viewed his approach as too mechanistic — focusing on automatic stimulus-response behavior while ignoring internal mental processes involved in learning.[3][4] These limitations highlighted the broader shortcomings of behaviorist models and contributed, alongside other developments, to the emergence of cognitive psychology,[4] which emphasized the role of thought, memory, and perception — areas Pavlov’s research did not explore.

Others, such as Carl Rogers, criticized behaviorism for being overly deterministic and based primarily on studies of animals, arguing that it failed to capture the complexity of human experience and personal agency.[5]

More detailed breakdown of the various criticisms can be found in our article here.

Impact on Psychology

Pavlov’s discovery of classical conditioning had a lasting impact on psychology, particularly on the development of behaviorism, which emphasized observable behavior over internal mental states. His stimulus-response framework helped shift psychology toward a more scientific and measurable study of behavior. This approach laid the foundation for psychologists like John Watson and B.F. Skinner, who expanded on Pavlov’s ideas to develop modern theories of learning.[6][7]

Beyond theory, Pavlov’s principles influenced practical fields such as therapy and marketing. For example, techniques like systematic desensitization, developed by Joseph Wolpe, applied classical conditioning to treat phobias and anxiety.[8] In addition, classical conditioning principles have also been used to explain how emotional associations influence attitudes in marketing and advertising, where products are paired with positive stimuli to shape consumer preferences.[9]

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

Pavlov received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904 for his research on digestion, particularly how saliva and gastric juices respond to food stimuli.[10] Although unrelated to classical conditioning, the award cemented his status as a leading scientist. He continued to conduct research and teach actively for decades, earning recognition from institutions worldwide for his contributions to both physiology and psychology.

Pavlov passed away on February 27, 1936, at the age of 86. His work remains foundational in psychology, influencing fields such as education, behavioral therapy, and scientific approaches to learning and behavior.

References

- Gantt, W. H. (2025, March 17). Ivan Pavlov. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ivan-Pavlov

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex (G. V. Anrep, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1901)

- Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It’s not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.43.3.151

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20(2), 158–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074428

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Appleton-Century.

- Wolpe, J. (1958). Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford University Press.

- Staats, A. W., & Staats, C. K. (1958). Attitudes established by classical conditioning. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 57(1), 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0042775

- Nobel Prize Outreach AB. (n.d.). The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1904 – Summary. NobelPrize.org. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1904/summary/