Classical Conditioning: How We Learn Through Association

Quick Summary

Classical conditioning (aka Pavlovian conditioning) is a type of learning where an organism forms an association between a neutral stimulus and one that naturally causes a reaction. Over time, the neutral stimulus alone can produce the response. Discovered by Ivan Pavlov in the early 1900s, classical conditioning remains a central concept in psychology, explaining how behaviors, emotions, and habits are shaped through repeated experiences.

What is Classical Conditioning?

Classical conditioning is a foundational concept in psychology that explains how certain behaviors and emotional reactions are learned through repeated experiences. It shows that even automatic responses, such as salivating, flinching, or feeling anxious, can develop through the association of one event with another, rather than occurring naturally from birth.

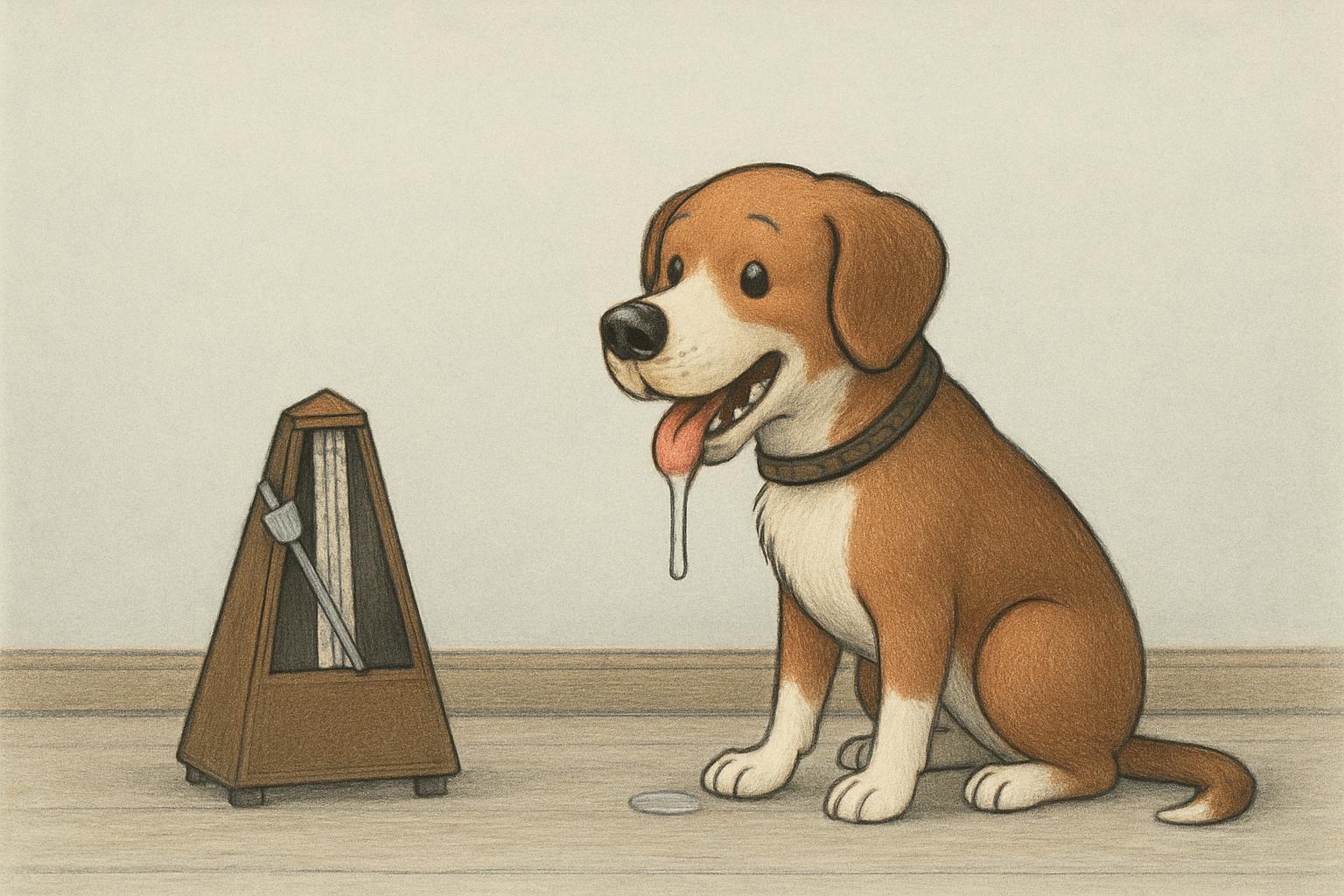

Pavlov’s Discovery of Classical Conditioning: The Dog Experiment

Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, discovered classical conditioning (aka Pavlovian conditioning) while studying digestion in dogs. He observed that dogs would salivate not only when food was presented but also when they encountered sights or sounds associated with feeding.

To explore this, Pavlov designed an experiment where he repeatedly sounded a metronome before giving the dogs food. Initially, the metronome — a neutral stimulus — had no effect. However, after several repetitions, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the metronome alone.[1]

This demonstrated that a neutral stimulus could, through association, trigger a natural reflex, a process that became known as classical conditioning.

Although Pavlov’s research focused on animals, the same learning principles apply broadly to humans as well.

Key Concepts of Classical Conditioning

Several important terms describe how classical conditioning occurs:

- Unconditioned Stimulus (UCS):

A stimulus that naturally produces a reaction without any prior learning.

Example: Food causing a dog to salivate. - Unconditioned Response (UCR):

The natural, automatic reaction triggered by the unconditioned stimulus.

Example: Salivating when food is presented. - Neutral Stimulus (NS):

A stimulus that initially has no effect on the desired response.

Example: The ticking of a metronome before training. - Conditioned Stimulus (CS):

A stimulus that was once neutral but, after being paired with the unconditioned stimulus, triggers a learned response.

Example: The metronome after it becomes associated with food. - Conditioned Response (CR), aka Pavlovian response:

The learned reaction to the conditioned stimulus.

Example: Salivating at the sound of the metronome.

Through repeated pairings, the neutral stimulus becomes linked to the unconditioned stimulus, eventually triggering the response on its own.

The Process of Classical Conditioning

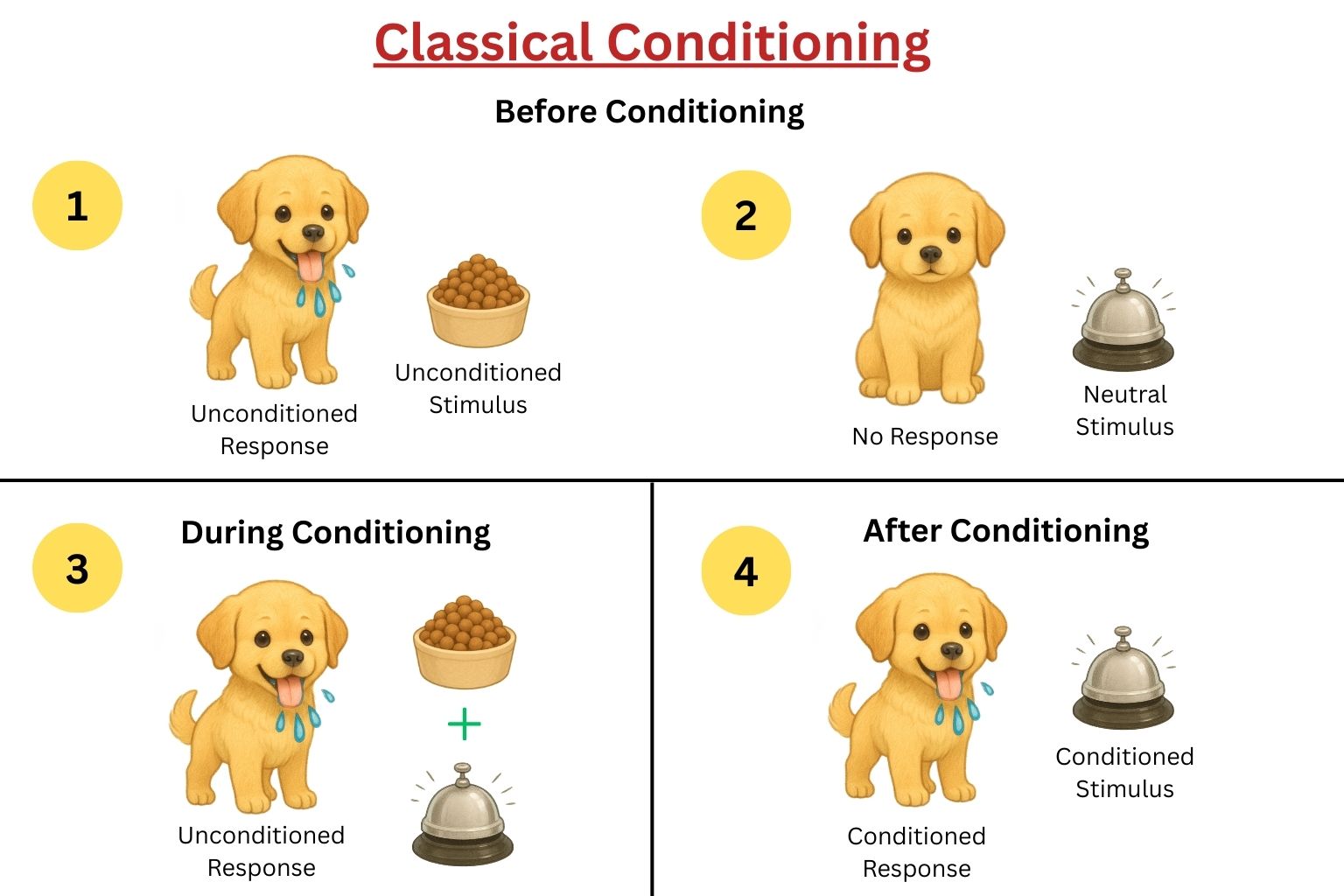

The learning process in classical conditioning typically unfolds across three stages:

1. Before Conditioning

- The unconditioned stimulus naturally triggers the unconditioned response.

Example: Food (UCS) leads to salivation (UCR). - The neutral stimulus produces no relevant response yet.

Example: The metronome (NS) does not cause salivation.

2. During Conditioning

- The neutral stimulus is repeatedly presented together with the unconditioned stimulus.

- Over time, the organism starts to associate them.

Example: Metronome (NS) paired with food (UCS) causes salivation (UCR).

3. After Conditioning

- The neutral stimulus becomes a conditioned stimulus.

- Now, the organism responds to the conditioned stimulus alone.

Example: Hearing the metronome (CS) causes salivation (CR) even without food present.

Real-world example:

If a person gets food poisoning from eating a specific dish, they might later feel nauseous just smelling or seeing that food again.

Major Phenomena in Classical Conditioning

Several important processes shape how classical conditioning forms and changes over time:

1. Acquisition

Acquisition is the initial phase of learning, where the organism first begins to associate the neutral stimulus with the unconditioned stimulus. The closer in time and the more consistent the pairings are, the faster and stronger the association becomes.

Example: A dog quickly learns that the sound of a can opener signals food after a few repetitions.

2. Extinction

Extinction occurs when the conditioned stimulus is presented repeatedly without the unconditioned stimulus, leading the learned response to gradually weaken and eventually stop.

Example: If the metronome sounds many times without food following, the dog’s salivation response decreases and may eventually disappear.

However, extinction does not always erase the learning entirely.

3. Spontaneous Recovery

Spontaneous recovery refers to the sudden reappearance of a previously extinguished conditioned response after some time without exposure to the conditioned stimulus.

Example: A dog that stopped salivating to the metronome may suddenly salivate again when it hears the metronome after a few days.

This suggests that learned associations may persist beneath the surface, even after they seem to fade.

4. Generalization

Generalization occurs when stimuli similar to the original conditioned stimulus also trigger the conditioned response.

Example: A dog conditioned to salivate to a metronome might also salivate when hearing a ticking clock.

Generalization allows learned behaviors to extend to similar situations.

5. Discrimination

Discrimination is the process by which an organism learns to distinguish between the conditioned stimulus and other stimuli.

Example:

A dog salivates only to the sound of the metronome but not to other sounds like a bell.

Discrimination refines behavior, allowing more accurate responses to specific stimuli.

Examples of Classical Conditioning in Everyday Life

Classical conditioning influences many aspects of daily experience:

- Emotional Reactions:

Someone stung by a wasp may later feel fear when hearing any buzzing insect. - Phobia Formation:

A person who falls from a height may later experience anxiety near balconies, rooftops, or ladders. - Medical Situations:

Chemotherapy patients may feel nauseous just entering a hospital due to past associations with treatment. - Advertising Techniques:

Brands often pair their products with positive imagery or music to create emotional associations. - Educational Settings:

Students who experience repeated stress during exams may develop anxiety entering exam rooms. - Animal Training:

Pets often learn to associate the sound of keys or a leash with specific activities like walks.

Classical conditioning often shapes behaviors and feelings automatically, without conscious thought.

Classical Conditioning vs. Operant Conditioning

Though this post focuses on classical conditioning, it’s useful to briefly contrast it with operant conditioning, another major learning theory often taught alongside it. Introduced by B.F. Skinner, operant conditioning involves learning through consequences, while classical conditioning is based on associations between stimuli and automatic responses.

Key Differences:

| Feature | Classical Conditioning | Operant Conditioning |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior Type | Involuntary, automatic responses | Voluntary behaviors shaped by consequences |

| Learning Process | Association between two stimuli | Behavior modified by reinforcement or punishment |

| Example | Feeling fear during a thunderstorm | Studying more to earn higher grades |

Reinforcement and Punishment in Operant Conditioning:

- Positive reinforcement: Adding a pleasant stimulus to encourage behavior (e.g., giving praise).

- Negative reinforcement: Removing an unpleasant stimulus to encourage behavior (e.g., silencing an alarm when a task is completed).

- Punishment: Applying a negative outcome to discourage behavior (e.g., taking away privileges).

On the other hand, classical conditioning involves no rewards or punishments — it focuses purely on associations between events.

Criticisms of Classical Conditioning

While classical conditioning remains a central idea in psychology, several influential psychologists have raised important criticisms about its limitations.

1. Overreliance on Stimulus-Response Models

Robert Rescorla argued that traditional interpretations of classical conditioning were too simplistic. His research demonstrated that learning depends not just on the pairing of stimuli, but on the informational value and predictiveness of the conditioned stimulus. According to Rescorla, animals and humans form expectations based on contingencies — meaning conditioning involves cognitive processing, not just automatic associations.[2]

2. Neglect of Internal Cognitive Processes

Albert Bandura also critiqued classical conditioning as part of a broader challenge to behaviorist models. He emphasized that learning involves more than external stimuli and observable behavior; it also requires internal processes like attention, memory, and motivation. Bandura’s social cognitive theory highlighted the active role of individuals in shaping their own learning, a dynamic that classical conditioning overlooks.[3]

3. Failure to Acknowledge Human Experience and Free Will

Carl Rogers, a major figure in humanistic psychology, criticized behaviorism — including classical conditioning — for its deterministic view of human behavior. He believed that this approach failed to account for individual agency, conscious experience, and the innate drive toward self-actualization. In his view, reducing people to passive responders to stimuli ignores the richness and uniqueness of human experience.[4]

Despite these criticisms, classical conditioning remains a major contribution to understanding how learning and behavior develop.

Conclusion

Classical conditioning revealed how simple associations between experiences can shape behavior and emotions. Ivan Pavlov’s experiments with dogs demonstrated that even automatic reactions could be learned through repeated pairings of stimuli, challenging earlier views that such behaviors were purely instinctual.

Today, the principles of classical conditioning continue to influence fields such as education, therapy, and marketing. Understanding how these associations form helps explain not only basic learning processes but also the development of emotional responses and habits in everyday life.

To learn more about Ivan Pavlov and the discovery of classical conditioning, you can visit our detailed page on Ivan Pavlov.

References

- Pavlov, I. P. (1927). Conditioned reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex (G. V. Anrep, Trans.). Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1901)

- Rescorla, R. A. (1988). Pavlovian conditioning: It’s not what you think it is. American Psychologist, 43(3), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.43.3.151

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall.

- Rogers, C. R. (1961). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.